THE HISTORY OF MUZAK

Muzak. It’s a word that most people of a certain age at least vaguely recognize. For many, Muzak is associated with instrumental easy-listening covers, waiting on hold, and elevator music.

Alongside other companies like Band-aid and Kleenex, the brand recognition is so strong that it has become synonymous with the product it sells.

But is Muzak really just “elevator music”?

The answer to that question is… well… no.

There is actually quite a surprising story behind the history of the Muzak company.

Let’s start at the beginning. Where does the name Muzak come from?

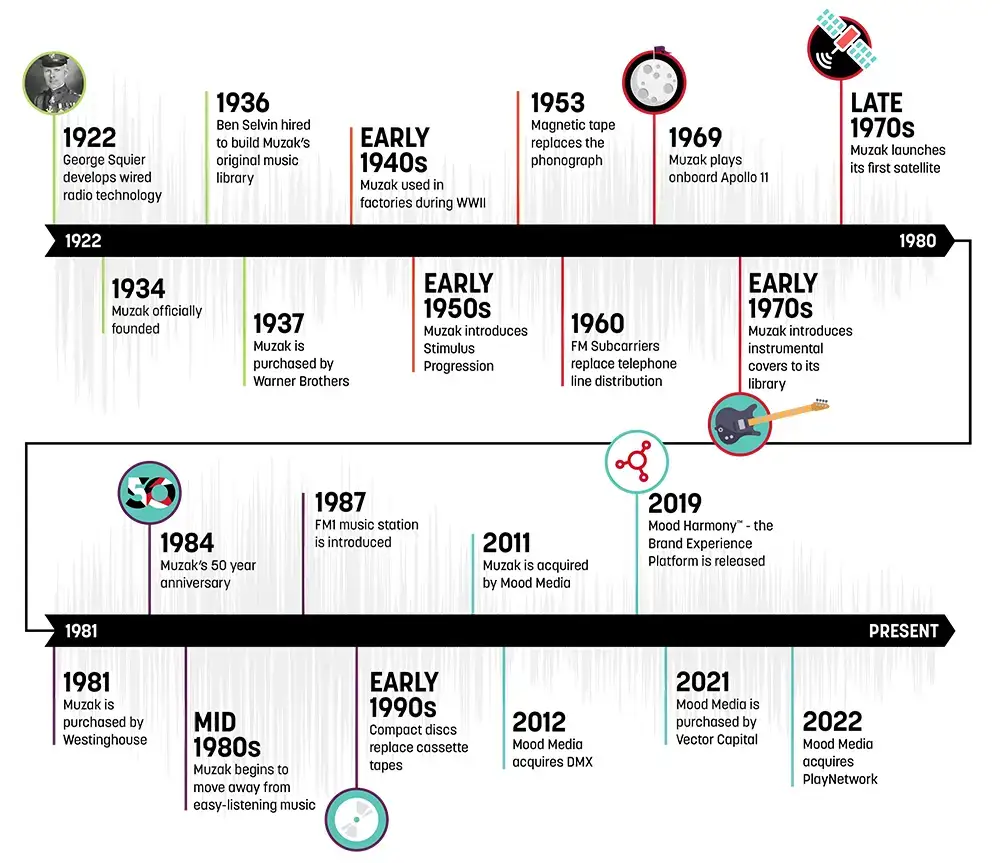

When General George Squier founded the company in 1934, he combined the name of his favorite technology company of the time with the word “music” to create Muzak. Music plus Kodak equals Muzak.

GEORGE SQUIER AND THE CREATION OF MUZAK

Born in Michigan in 1865, General George Squier was a scientist, an inventor, and a Signal Corp Officer. Throughout his military career, Squier served as a military attache, and he later was named head of the Aviation Section of the Signal Corp. As Chief Signal Officer, he contributed significant research and advancements in equipment. His inventive mind would continue down this creative path, specifically in the field of information transmission.

In the early 1920s, Squier discovered a method of transmitting information via electrical wires and realized that this new method could be used to distribute music. When tuned to the correct frequency, a phonograph at one end of the line could transmit music to receivers on the other end. At the time, music was only played via AM radio transmissions. But radio equipment was temperamental and expensive. Squier was granted several patents for his ideas, realizing that wire transmission had great potential for delivering music to a large audience. He sold these patents to a utility conglomerate called the North American Radio Company, and a new company was formed called Wired Radio Inc. The plan was to sell music subscriptions to the power company’s existing utility customers.

And in 1934, the music subscription service known as Muzak was created.

But there was just one problem.

General Squier and Wired Radio Inc. had the technology, but no music.

TRANSCRIPTION MUSIC SERVICES

Even in the 1930s, music licensing was a difficult beast to tame. At the time, music played on the radio was broadcast live, while recorded music was only licensed for personal use at home on gramophones. For Muzak to succeed, they needed to find a way to legally broadcast their music service. The solution to this problem was a process called “transcription.” Electronic transcription was a then-new process that allowed for higher-quality recordings than what was typically available. These recordings were longer in length and used primarily for broadcast purposes. Generally speaking, the use of eclectic transcription was geared toward recording live radio programs, as well as commercials and jingles. However, this meant that broadcasters were only allowed to distribute music and other recordings if they were recorded specifically for airplay and not for personal consumption. Muzak saw this as their opportunity to create a catalog of music recorded specifically for their new broadcast technology. But General Squier and his team were scientists and engineers. They didn’t know anything about the music industry, certainly not enough to build an entire library.

Enter – Ben Selvin.

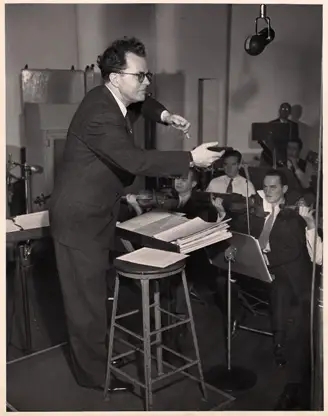

THE FIRST MUZAK MUSIC RECORDINGS

Born in 1898, Benjamin Bernard Selvin was an award winning musician, bandleader, and record producer. He was hailed as a music prodigy and would become known as the “Dean of Record Music.”

Selvin began his professional music career at the age of fifteen playing fiddle at night clubs in New York City. By the time he was twenty-one, he was leading a dance band called The Novelty Orchestra. Though relatively unknown now, The Novelty Orchestra released what was considered one of the best selling popular songs at the time – “Dardanella.” Released in 1919, “Dardanella” would go on to sell hundreds of thousands of copies worldwide of both records and sheet music. Selvin and his many bands were constantly performing and appearing on radio broadcasts. He also served as an executive for record companies, overseeing thousands of recording sessions with some of the top musicians of the era like Al Jolson, Bing Crosby, Glenn Miller, and Irving Berlin to name a few.

Due to his extensive resume and connections in the music industry, Selvin was the perfect candidate for helping build Muzak’s music library. He was hired as Chief Music Programmer in 1936. Again, the music available for purchase at the time was not licensed for broadcast. So what did they do? They recorded their own.

By the 1940s, Muzak’s exclusive transcription library totalled over 7,500 recordings, all available and licensed for broadcast into homes and businesses across the country.

*An interesting side note: These recordings still belong to Muzak (now Mood Media) and have moved with the company over their many relocations. This library of records has moved from New York to Seattle and is currently archived in Ft. Mill, South Carolina. Many of the recordings remain untouched to this day. Alongside the recordings are notebooks containing detailed information about the recording sessions, including track listings, outtakes, personnel listings, and sales pitches, dating from the 1930s through the 1970s.

THE FIRST MUZAK RADIO BROADCASTS

In 1934, Muzak broadcasted music to their first customers, a group of residents in Cleveland, Ohio. The cost was $1.50 a month for three channels of audio consisting of music and news. Breaking into the residential sector proved to be more difficult than expected. It was soon realized that the competition against commercial radio was too much of a fight. Though Muzak wasn’t without its fans. A man in Florida named Irving Wexler was quoted as saying, “I have Muzak in every room of my home. Twenty-four hours a day. We sleep with it on, watch TV with it on. I never allow it to be turned off, because I know that music has a therapeutic effect.”

Sadly, General Squier passed away in 1934 before seeing the true potential of his technology.

After Squier’s passing, ownership of the Muzak company changed hands a few times, including a brief ownership by Warner Brothers. Muzak had found minor success but struggled to keep up with traditional AM radio stations. It was during the height of WWII when a man named William Benton would take over ownership of Muzak. He was the driving force behind Muzak’s push into factories during the war, and he would usher the company into its next era of success in the 40s and 50s.

MUZAK AND EARLY RADIO

William Burnett Benton was already a success when he took over ownership of Muzak. Born in 1900 in Minnesota, Benton was a Yale graduate, advertising guru, encyclopedia publisher, and politician. In 1929 he founded Benton & Bowles advertising agency with his partner, Chester Bowles. Their agency would be best known for the creation of soap operas. Soaps were originally created as radio programs sponsored by soap manufacturers – hence the name. Benton & Bowles radio division would eventually produce three of the most popular radio programs on air in the 1930s.

Benton saw the potential in Muzak. While serving as vice-president of the University of Chicago, he took over full ownership of the company in 1939. Drawing on his advertising and marketing background, Benton put lots of effort into research to help bolster Muzak’s efforts.

THE EFFECTS OF MUSIC ON WORKFORCE PSYCHOLOGY

There was a growing interest in workforce psychology in the 1930s. The concept of ergonomics started to emerge in the workplace. Businesses were finding ways to humanize work areas and increase productivity. On a similar note, studies began to emerge on the effects of music on human psychology. A study from Stevens Institute of Technology in New Jersey showed that music in the workplace reduced absenteeism and worker turnover in employees by a significant margin. Around the same time, musicologists like Paul Nettl and Theodore Adorno were studying the effects of music, as well. This growing interest in the science behind music, especially when concerned with its effects on the workforce, helped Muzak gain traction.

By the end of 1934, Muzak began to market their radio services to restaurants and hotels in New York City. And yes, elevators, too. It was a fairly common practice to play music in elevators to both soothe passengers and pass the time since elevators were not as smooth or as fast as they are today.

William Benton pushed for Muzak’s expansion into factories and other industrial areas to boost employee productivity. This introduction of music in the workplace was the spark that would ignite the Muzak business strategy.

MUSIC FOR BUSINESS AND WWII

A major factor in Muzak’s growth came in 1939 due to the beginning of World War II. The large growth in industrial production during the war was a major window of opportunity. Thousands of factories dedicated to wartime industries were wired for Muzak commercial music services. Employee morale was boosted with the sounds of patriotic music like John Phillip Sousa marches and inspiring messaging from President Roosevelt and Winston Churchill.

In fact, Muzak was so closely tied to the war efforts it even had a hand in developing secure speech technology for Allied communication. In effect, the war efforts allowed for a large-scale study of Muzak music playlists in the workplace with the goal of increasing worker productivity.

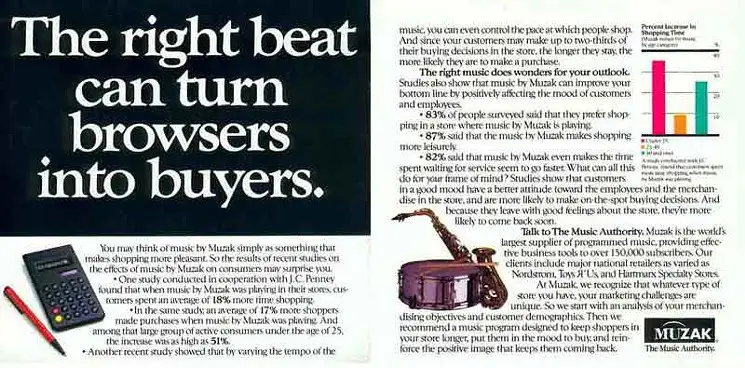

And it worked. Benton’s research strategies showed that music in the workplace had positive effects on the workforce. In fact, productivity went up by more than 10 percent at factories where Muzak music was played. Muzak was no longer regarded as background music, but functional music. Muzak had finally found its niche.

After WWII and throughout the 40s, Muzak would continue its push as functional music in the workplace. During the 1950s, they would introduce their next big idea called Stimulus Progression.

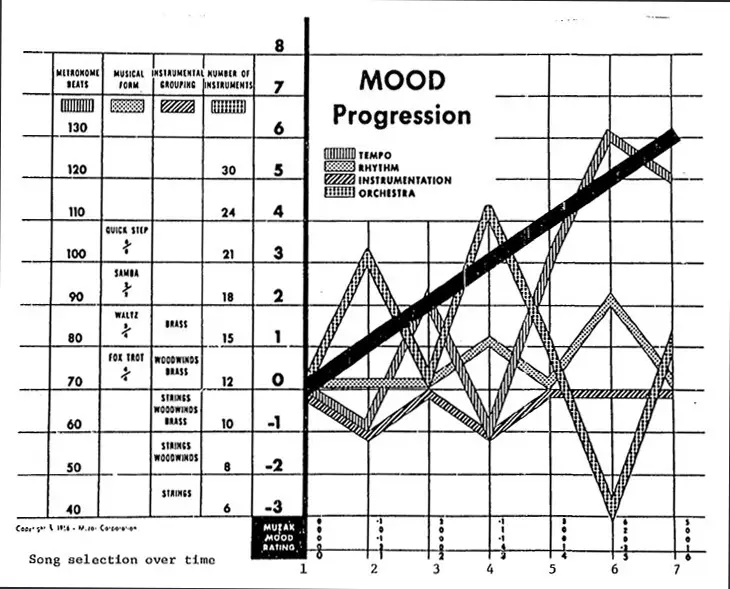

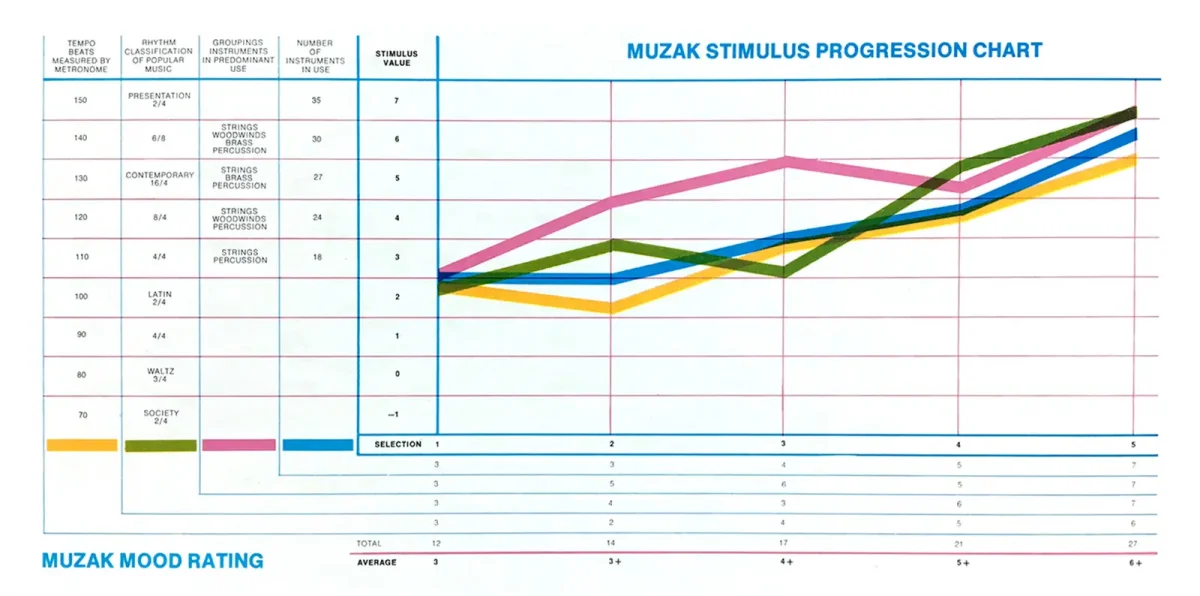

STIMULUS PROGRESSION – HOW MUSIC AFFECTS EMPLOYEES

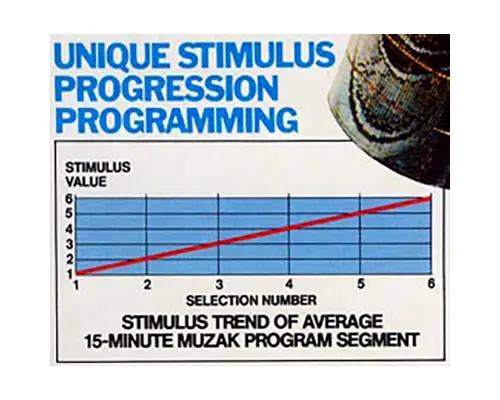

The basic concept of Stimulus Progression is the idea of changing the styles and tempos of music to counterbalance and influence the natural rhythms of the human body. Studies showed that employee production would dip during certain times of the day; before and after lunch, for example. Muzak playlists were then programmed against those patterns by playing more upbeat music during the slower times of the day, and vice versa. The style of music was typically light classical, heavy on string instrumentation, and as non-invasive as possible – all hallmarks of the Muzak sound.

In the 30s and 40s, when Muzak radio was delivered over telephone lines, it required an operator on the line twenty-four hours a day to keep the music playing. In the beginning, music was played off of records, and employees had to be ready at the machines to swap out discs to avoid any dead air time. As technology improved, records gave way to tape machines which could hold eight hours of continuous music. Telephone lines were eventually replaced by FM subcarriers.

MUZAK BUSINESS FRANCHISES

As the equipment became less expensive and demand for Muzak music services increased, companies were eager to get in on the game to boost their own profits. This made way for another major influence on Muzak’s rapid expansion during the 1950’s period of growth with the implementation of Muzak business franchises. Franchises allowed other companies to sell Muzak products while operating under their own business name.

These Muzak product resellers helped expand business into far corners of the country. Some of these franchisees still exist today and have continued to sell throughout the various Muzak ownership changes.

Surprisingly, several franchises were owned by famous celebrities like Bing Crosby and Bob Hope. Even President Lyndon B. Johnson owned a Muzak franchise called Texas Broadcasting, based in Austin, Texas. Johnson actually sold Muzak music services to the White House while President Eisenhower was in office.

In the 1960s, these franchises began to expand globally, as well, opening locations in Germany, England, France, Spain, Australia, and parts of South America.

SHRUGGING OFF THE STIGMA OF ELEVATOR MUSIC

The 60s were the Golden Age of advertising. Companies were starting to embrace the idea of not only being a business, but a brand. Companies now felt they had a story to tell and began to not just offer products, but experiences.

Now under the ownership of the Teleprompter Corporation, Muzak’s President Bing Muscio wanted to change the conversation around its stereotype as only easy listening music. Muscio felt that music was something that should draw the attention of the audience and not be relegated to the background.

Muzak’s first push into their new era began with introducing instrumental covers of popular songs by well known artists. The idea was to broaden the catalog of music by adding new genres and styles, while still applying the concepts of Stimulus Progression. In lieu of traditional covers, Muzak instead produced light classical covers of popular hits, thinking that lyrics and heavy instrumentation would only serve as a distraction in the workplace.

These easy-listening instrumental covers would become another hallmark of the Muzak style, one that many people still (incorrectly) associate with Muzak today.

With the sound of Muzak now spread worldwide, with it came the challenges of changing with the times. It was the 1970s. A time of rock and roll and rebellion. Especially for Americans living through touchpoints like Woodstock and the Vietnam War, the banality of easy-listening felt out of touch. Muzak would spend the next few decades working toward shrugging off that stigma.

There were several technological advances in the 1970s, as well. Muzak uploaded its large database of music onto computers for the first time, allowing for faster and easier catalog access. It was around this time that Muzak also launched its first broadcast satellite, making it the first satellite subscription radio service, beating out XM and Sirius radio by several decades.

MOVING BACKGROUND MUSIC TO THE FOREGROUND

In 1981 Teleprompeter was purchased by the Westinghouse Electric Company. Under this new ownership, a decision was made to finally leave the easy-listening background music behind.

Westinghouse saw the financial gain to be had from playing popular music. To facilitate the transition from background to foreground music, Muzak was merged with a major competitor called Yesco Inc.

Seattle based Yesco Inc. was founded in 1968 by Mark Torrance as a counter to Muzak’s music for business offerings. He used the elevator music stereotype against Muzak, and instead offered licensed soft-rock hits from major record companies and arranged them into playlists appropriate for the workplace. Yesco managed to build a reasonable share of the music for business industry and pioneered the idea that music could stand out in a place of business as opposed to being pushed into the background.

In 1986, Muzak merged with Yesco and relocated from its 1936 home in New York to Seattle with Mark Torrance serving as president. With this merger came the introduction of FM1 – otherwise known as Foreground Music One.

With music now pushed to the forefront, the relationship of Muzak playlists to its audience transformed from passive to dynamic. Instead of playing instrumental covers, Muzak stations would broadcast original music by popular artists.

What differentiates this from the original Muzak radio broadcasts goes back to the issue of licensing. As we’ve mentioned, up to this point Muzak was not just broadcasting music, but also recording original tracks. But the 80s was now the era of MTV which shook up the world of production and broadcast rights, making it easier for companies like Muzak to obtain proper licensing rights needed to distribute music from popular artists.

By the end of the 1980s and into the 1990s, Muzak would see several more ownership and technological changes that helped shape the business. Music delivery shifted from cassette tapes to compact discs. A partnership formed with Dish Network and offered up to 60 new music channels in residential homes. Muzak also expanded its offerings beyond just music, such as Audio Marketing Services like on-hold and instore messaging, Ad-parting, Drive-thru services, TV for business, and even those little red scrolling LED signs along the sides of buildings.

Mark Torrance

MUZAK EXPANSION, RELOCATION, AND REBRANDING

But the biggest change was a philosophical one. Muzak’s relocation had put the business right in the heart of the Seattle music scene during the 1990s, attracting many musicians looking for steady work in the music industry. This influx of creative minds shifted how Muzak saw itself as a brand. The company started bringing attention to the individual employees who put together the playlists. They were promoted as more than just DJs arranging song orders. They instead were viewed as musicians and artists who harnessed the emotional power of music and carefully curated branded playlists. These Audio Architects, as they were called, became the face of the company. This new focus on expertly designed playlists, along with a new logo and a new attitude, helped to shed some of the elevator music stigma of the brand and instead position the company as leaders in the music industry.

WHERE IS MUZAK TODAY?

In 1999 Capstar purchased Muzak and it was merged once again, this time with Audio Communications based out of Orlando, Florida and a relocation to Fort Mill, South Carolina. In 2011, Muzak was purchased by a company known as Mood Media.

Mood Media began in 2004 as a Toronto, Canada based company called Fluid Music. Fluid Music rebranded as Mood Media in 2010 after taking over a European media group of the same name. In addition to purchasing Muzak in 2011, it also acquired Muzak’s largest competitor at the time, DMX (based in Austin, TX), in 2012, and by 2013 all entities were working — and continue to work — under the Mood Media brand name. Additional, more recent acquisitions include Technomedia, focus4media, South Central AV, and PlayNetwork. In January 2021, Mood Media was acquired by Vector Capital, a San Francisco-based private-equity firm that focuses exclusively on technology companies.

Through its series of acquisitions and positive growth, Mood Media is now the world’s leading in-store media solutions provider with a global presence that extends across 180 countries. It has moved well beyond music and messaging and offers a holistic set of media solutions that are all designed to engage, elevate and maximize Customer Experiences. These solutions include professionally designed music playlists, custom music for business, digital signage and video solutions, on-hold and in-store messaging, scent marketing, drive-thru technology,and audiovisual systems.

MUZAK MILESTONES

- archive.seattletimes.com/archive/?date=19991124&slug=2997406

- historylink.org/File/10073

- af.mil/About-Us/Biographies/Display/Article/2220886/major-general-george-owen-squier/

- trivia-library.com/a/history-of-muzak-part-1-william-b-benton-invents-muzak.htm

- trivia-library.com/a/history-of-muzak-part-1-william-b-benton-invents-muzak.htm

- syncopatedtimes.com/ben-selvin-1898-1980/

- secondhandsongs.com/artist/7744/originals

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electrical_transcription

- fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/muzak-inc-history/

- wikipedia.org/wiki/Electrical_transcription

- historyofinformation.com/detail.php?id=3366

- nytimes.com/1973/03/19/archives/william-benton-dies-here-at-72-leader-in-politics-and-education.html

- nytimes.com/1975/03/16/archives/muzaks-global-music-its-soothing-to-a-secretary-pabulum-to-a-critic.html

- prnewswire.com/news-releases/mood-media-to-acquire-muzak-for-us345-million-118583859.html

- wqxr.org/story/history-muzak-where-did-all-elevator-music-go/

- cloudcovermusic.com/music-for-business/muzak/#muzak-for-enterprise

- cabinetmagazine.org/issues/7/min.php

- atlasobscura.com/articles/history-of-elevator-music

- company-histories.com/Muzak-Inc-Company-History.html